The Changing Face of Montague: looking to the past to look to the future

In the third and final instalment of this three-part series, Southbank News speaks with the astonishing Elva Keily, one of Montague’s original residents, and looks ahead to what lies in store for the renaissance of this once forgotten suburb.

Closing in on her 95th birthday, Elva was born the last of six children, five girls and one boy, in their single-fronted cottage home at 33 Buckhurst St.

Her encyclopaedic knowledge of what she calls the “old Montague” is something to behold, recalling her early years in the grip of the Great Depression with flawless memory.

“It was a tough time,” Elva told Southbank News from her new home in Port Melbourne. Despite its challenges, it was a time she felt lucky to have lived through it in order to cherish the life she and her growing family live now.

“I was very fortunate, especially as my father had a job,” Elva said. “I saw people getting put out on the street, not realising why for [how] much later in life, but it was because they couldn’t pay the rent.”

“Our parents owned our house, so we couldn’t be put out, but it got to the stage where my brother had to sleep on the front veranda with a canvas blind; but that wasn’t unusual in the area.”

“There would be kids coming to school, particularly boys, kicking the football in the middle of winter with no shoes on. We just thought they were tough, but thinking now, they wouldn’t have been able to afford shoes.”

Born to mother Helen and father Samuel, a factory worker at the British Australian Tobacco Company in A’Beckett St, Elva recalls how her father would bring back his allowance of tobacco and the six children would all roll cigarettes.

Yes, 1930s Montague was considered a rough place in an even harsher era; however, Elva said the sense of belonging and unity among locals was what made this community so great.

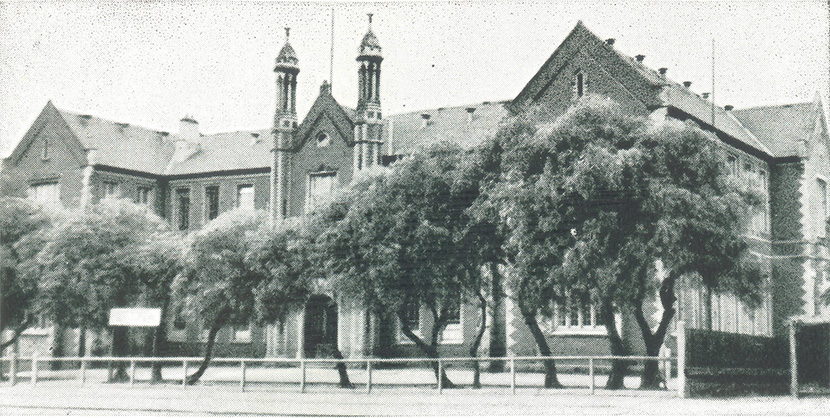

As a young child Elva attended Lady Northcote Kindergarten on Buckhurst St, then the now closed Dorcas St State School in South Melbourne, where her snow-white hair would become a talking point for students.

“Going to dances at the South Melbourne Catholic Church, we would break for morning tea and go for an ice cream from ‘Zacko’ the ice cream vendor,” she said. “This cocky young fella asked me how much peroxide was, so I grabbed my ice cream and shoved it in his face.”

“I now go to a meet-up group called The Burrough Club at the Uniting Church across the road was where Dorcas St State School was before Jeff Kennett got his hands on it and sold it off.”

Elva said the thriving industrial neighbourhood, headed by major manufacturers like Dunlop Rubber Factory, Lever and Kitchen and the nearby Allen’s Confectionary and Hoadley Chocolates, famous for the widely popular Violet Crumble, created a hive of activity during the 1920s and 1930s.

With her heart still firmly entrenched with fond memories of years gone by, Elva still keeps her eyes on what the “new Montague” will look like as part of the Fishermans Bend urban renewal project.

Also with an eye on Australia’s largest urban renewal project is David “Woody” Woods, founder and blacksmith at Thistlethwaite St’s traditional forge and sculpture studio, Bent Metal.

Woody’s studio is the site of Montague’s first, and what is presumed, only bakery, once servicing the whole suburb.

“I started Bent Metal in 1991 in a little house on Punt Rd, Prahran, then moved to a spot down an alleyway off Thistlethwaite St,” Woody said.

“The woman who owned the bakery got her daughter to come to me and said I heard were looking for a factory.”

“I knew this place because there were six to eight people living here, it was known as a bit of a hippy commune. I had been to a few parties here in my time, so I said, ‘sure’.”

“South Melbourne at that time was great. This street and Montague St was all mechanics, but there were other creative people dotted around; it was what attracted me to the area.”

Woody, who has now been at his current Thistlethwaite St studio for more than two decades, is one of the only traditionally trained blacksmiths in Melbourne’s inner-city.

With works like the St Kilda Bontanical Gardens gates, or his piece at Acland Square, Woody’s mixture of sculpture and domestic projects often take him to every corner of the state.

He said a lot of specialist craftspeople and artisans have been forced out of the inner-city due to a lack of affordability.

Woody speaks of an impending doom felt by businesses around him as developers begin to snatch up land in anticipation of flood of low-, medium-, and high-rise development earmarked in the Fishermans Bend framework.

“Creative people are getting shoved out of the inner-city, it’s becoming increasingly hard to find places that are affordable and have access to services,” he said.

“I had visions of a really cool baker moving in here and getting the mid-1800s oven working again, but I don’t see that happening.”

“The panel beaters next door have been there for 25 years, but they are on their way out. There are only a handful of businesses who have been in the area for longer than a decade or so.”

All of the businesses and locals interviewed during this series speak of Montague, as it was, and as it now is, with great affection.

There is seemingly an enormous cloud of uncertainty that sits above the businesses of Montague.

It forms the shape of the Fishermans Bend urban renewal, which still sits in its infancy in terms of shovel-ready change.

Can Fishermans Bend cater for 80,000 residents and 80,000 workers and still pay homage to an area steep in history?

What will happen to the dozens of mechanics, panel beaters, gyms, café and studios?

Can design and development include affordable spaces for artists and specialist craftspeople?

Paris has Montmarte, Chile has Valparaiso, and Copenhagen has Nørrebro, why can’t Melbourne have Montague? •

Caption: Original Montague resident Elva Keily, Bent Metal’s David “Woody” Woods and Dorcas St State School, 1930.

Sally Capp: one last chat as Lord Mayor of Melbourne

Download the Latest Edition

Download the Latest Edition